For intrepid travelers, the challenging terrain and mystical beauty of Saudi Arabia’s Empty Quarter beckon

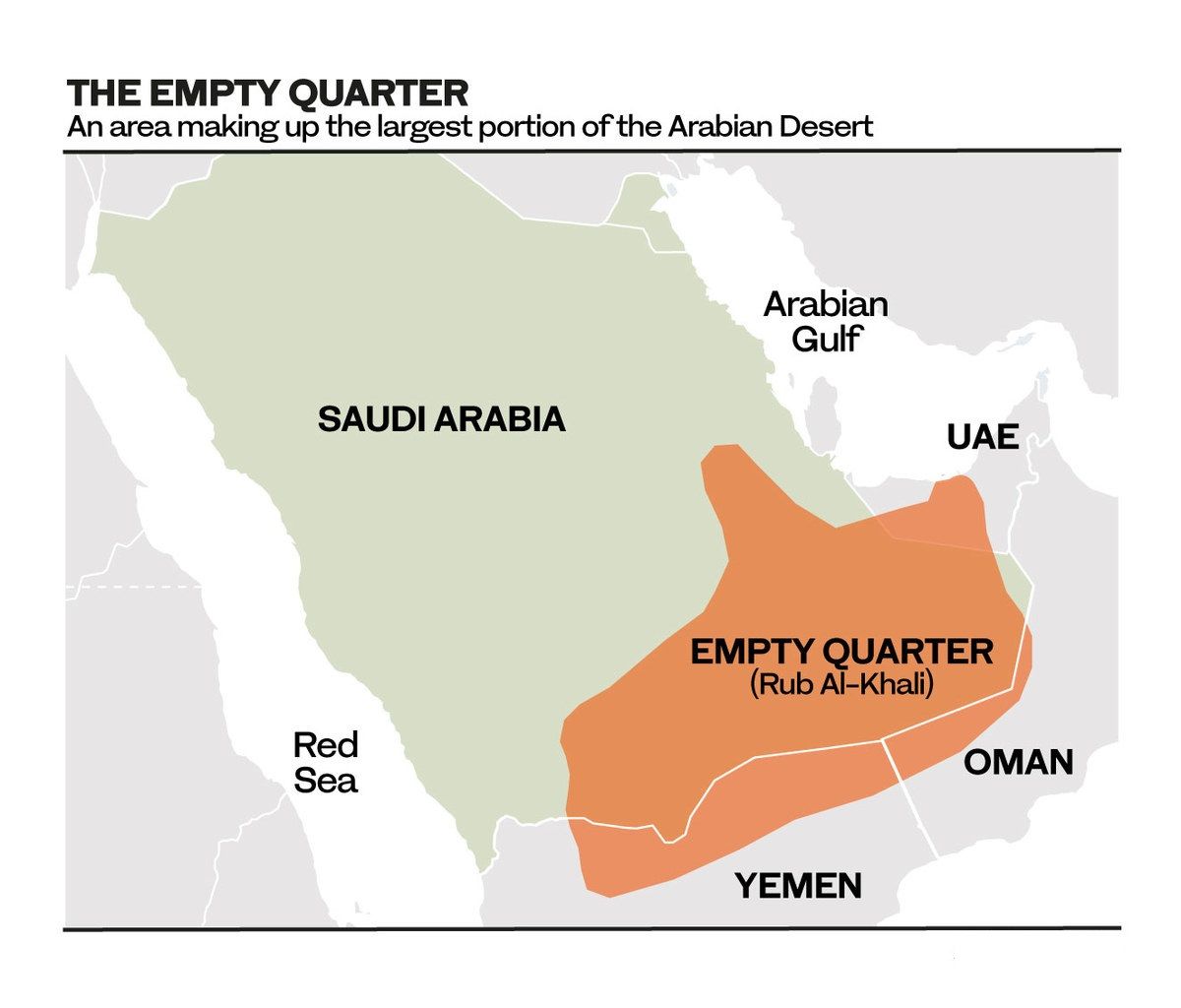

The largest segment of the world’s biggest sand desert, which ecompasses much of the southern third of the Arabian Peninsula, is located in Saudi Arabia, stretching to the south and east into Oman, the UAE and Yemen.

Throughout history men and women have been lured by the beauty of its undulating dunes, punctuated by rare patches of lush vegetation and palms. However, it was not until the early 20th century that the first recorded voyages across this beautiful yet dangerously vast landscape were first published.

The Empty Quarter occupies a special place in the Saudi consciousness. It was in this vast desert that King Abdulaziz bin Abdulrahman Al-Saud, Saudi Arabia’s founder and first monarch, made camp before capturing Riyadh from the rival Al-Rashid family in 1902, thereby establishing supremacy over the Najd region of central Arabia.

A team led by Omani-based British explorer Mark Evans trekked across the world’s largest sand desert in 2016.

A team led by Omani-based British explorer Mark Evans trekked across the world’s largest sand desert in 2016.

In 1930, Omani Sheikh Saleh bin Khalut and English explorer Bertram Thomas made the first recorded crossing of the Rub Al-Khali. Then, about two years later, the great English explorer Harry St. John Philby crossed the Empty Quarter on camelback.

For 20 years he dreamed of the crossing. He described it to his wife Dora as “this beastly obsession which has so completely sidetracked me for the best years of my life.”

He recorded his journey with precision, noting not only the natural landscape and its geology but also the moments of physical and mental struggle that it took to cross this seemingly infinite terrain, which covers 650,000 sq km, an area roughly the size of France.

Philby popularized the name “Empty Quarter,” claiming this was the term used by the Bedouin who dwelled there, owing to its vast, largely empty terrain, devoid of human settlements besides the shelters of the roaming Bedouin tribes, who still inhabit the region today.

To this day, it is believed that entering this desert without a guide is akin to suicide.

The Rub Al-Khali is characterized by a scarcity of water resources, a maze of sand dunes where it is easy to lose one’s way, and extreme heat. As one local saying goes: “One who can exit it, must be born again, while those inside, remain missing.”

The ancients once believed the Empty Quarter held a lost city — Ubar — one that Philby set out to uncover. It is said to be buried in the sand, having been destroyed by a natural disaster or, as legend has it, by God, for its occupants’ wickedness.

T.E. Lawrence, the British army officer and writer renowned for his role in the Arab Revolt against the Ottoman Empire during World War I, called Ubar the “Atlantis of the Sands” — a city, he wrote, “of immeasurable wealth, destroyed by God for arrogance, swallowed forever in the sands of the Rub Al-Khali desert.”

Saudi Riyadh-based Hattan Baraqan‘s Empty Quarter journey in 2019 organized by the Camel Club of Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Riyadh-based Hattan Baraqan‘s Empty Quarter journey in 2019 organized by the Camel Club of Saudi Arabia.

Both Philby and Thomas came to believe the city was nothing more than a myth. Unconvinced, however, British adventurer Sir Ranulph Fiennes co-led an expedition to find the lost city in 1991. Although the team uncovered evidence of a settlement in the vast waste, experts remain divided to this day over whether this was indeed the lost city of legend.

Now, as the Kingdom continues to open to the outside world, more excursions are taking place, guiding both Saudis and foreign travelers through this still largely unknown and challenging terrain.

While the Saudi Tourism Authority does not currently offer excursions to the area, a spokesperson told Arab News: “From historical mountain ranges to pristine beaches, Saudi has some of the most diverse landscapes, but perhaps none more iconic than its deserts.

“As one of the world’s largest deserts, it’s advised that the Empty Quarter is best visited with certified tour guides.”

However, for many locals who grew up on the edges of this forbidding expanse, the Empty Quarter is a place of tranquility.

“I miss the calmness and silence of the desert,” Mubarak Al-Hussain, from Sharurah, a town in Saudi Arabia’s Najran Province close to the Yemeni border, told Arab News.

US biker Jacb Argubright during the Stage 11 of the Dakar 2023, between Shaybah and Empty Quarter Marathon, in Saudi Arabia.

US biker Jacb Argubright during the Stage 11 of the Dakar 2023, between Shaybah and Empty Quarter Marathon, in Saudi Arabia.

“Every weekend my friends and family go to the desert.”

Al-Hussain, now based in Riyadh, where he works as the head of training at Arabius, one of the Kingdom’s premiere language and culture agencies, remembers fondly his hometown and the allure of the Rub’ Al-Khali.

He described how people from his town would go into the desert during the winter to find wood following a rain shower — an extremely rare occurrence. The trip would be arduous and dangerous and the wood would be heavy, adding extra weight to the car, making it more likely that they would become stuck in the sand.

Despite the challenges of the Rub Al-Khali, Al-Hussain speaks with passion about the beauty of his hometown and the spiritual richness of the desert. Indeed, the Empty Quarter has cast its spell on many.

In 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, an excursion led by the Saudi Camel Club took a group of men and women from various countries, including Australia, Germany, Japan and Colombia, and from across Saudi Arabia, on a journey across the Empty Quarter on camel back.

The club, established in 2017 by King Salman following the launch of the Kingdom’s social reform and economic diversification agenda, Vision 2030, is committed to preserving camel-riding as part of Saudi Arabia’s distinctive heritage.

Saudi Riyadh-based Hattan Baraqan‘s Empty Quarter journey in 2019 organized by the Camel Club of Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Riyadh-based Hattan Baraqan‘s Empty Quarter journey in 2019 organized by the Camel Club of Saudi Arabia.

Crossing the Empty Quarter was one of the club’s initiatives — one that emulated traditional Bedouin culture while taking part in an endurance excursion through one of the most beautiful and mysterious natural wonders of the Kingdom.

Riyadh-based Saudi national Hattan Baraqan was among them. “I am an adventurous person and had always wanted to visit the Empty Quarter,” he told Arab News.

The group began its voyage in the southernmost part of the country — an area Baraqan had never been to before. Along with 80 others, he embarked on a crossing of the Empty Quarter that lasted 26 days.

“We went through a lot,” he said. “It was really, really extreme — more than we expected. I think it was also more than the organizers expected.”

The caravan finished with 67 riders, with 13 dropping out due to injuries and exhaustion.

“At times it was too hot during the day and at other times there were too many sandstorms,” Baraqan said. “At night and during the morning it was very cold. We would ride for eight or nine hours on a camel each day.”

It was during this journey that Baraqan came to appreciate the character and resilience of the camel. “A camel is a master of him or herself,” he said. “They are also very smart.”

US biker Howes Kyler (L) and French biker Adrien Van Beveren compete

during the Stage 11 of the Dakar 2023, between Shaybah and Empty Quarter

Marathon, in Saudi Arabia.

US biker Howes Kyler (L) and French biker Adrien Van Beveren compete

during the Stage 11 of the Dakar 2023, between Shaybah and Empty Quarter

Marathon, in Saudi Arabia.

At one point, Baraqan says that the group was very low in resources, especially food and water. “We had no technology, no distractions, just ourselves and the desert and the camels,” he said. “It was really tough, but never in my life have I breathed such clean air.

“It was a trip that allowed us to reflect on how human beings lived long ago. We gained a lot of wisdom and began to appreciate small things. We were surprised one morning to wake up and see butterflies.”

The journey through Rub Al-Khali, as Baraqan recounts, was filled with enriching moments of discovery. Once the group met a shepherd who lived in isolation. Other times they uncovered areas filled with greenery, wells and animals.

“It was more beautiful than I could have imagined,” he said. “It is a very peaceful place. The Empty Quarter is not empty at all. It is full of faith.”