Being Muslim and American in the nation's heartland

The oldest surviving place of worship for Muslims in the United States reflects the diverse community that defines what it can mean to be both Muslim and American.

CEDAR RAPIDS, Iowa: The oldest surviving place of worship for Muslims in the United States is a white clapboard building on a grassy corner plot, as unassumingly Midwestern as its neighboring houses in Cedar Rapids – except for a dome.

The descendants of Lebanese immigrants who constructed ‘the Mother Mosque’ almost a century ago — along with newcomers from Afghanistan, East Africa and beyond — are defining what it can mean to be both Muslim and American in the nation’s heartland just as heightened conflicts in the Middle East fuel tensions over immigration and Islam in the United States.

Standing by the door in a gold-embroidered black robe, Fatima Igram Smejkal greeted the faithful with a cheerful ‘salaam’ as they hurried into the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids for Friday prayers.

In 1934, her family helped open what the National Register of Historic Places calls ‘the first building designed and constructed specifically as a house of worship for Muslims in the United States.’

Muslims attend Friday prayer at the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids on Friday, Aug. 8, 2025, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

(AP)

The community now gathers in the Islamic Center.

It was built in the 1970s when they became too many for the Mother Mosque’s living-room-sized prayer hall, and now they’re have outgrown its prayer hall, as well.

Hundreds of fifth-generation Muslim Iowans, recent refugees and migrants pray on industrial carpets rolled onto the gym’s basketball court — the elderly on walkers, babies in car seats, women in headscarves and men sporting headgear from African kufi and Afghan pakol caps to baseball hats.

This physical space where diverse groups gather helps sustain community as immigrants try to preserve their heritage while assimilating into US culture and society.

‘Mother Mosque’

Tens of thousands of young men, both Christians and Muslims, settled in booming Midwestern towns after fleeing the Ottoman Empire, many with little more than a Bible or a Qur’an in their bags.

They often worked selling housewares off their backs to widely scattered farms, earning enough to buy horses and buggies, and then opened grocery stores.

GROWING UP MUSLIM IN AMERICA

Muslims sometimes faced institutional discrimination.

After serving in World War II, Smejkal’s father, Abdallah Igram, successfully campaigned for soldiers’ dog tags to include Muslim as an option, along with Catholic, Protestant and Jewish.

But in Cedar Rapids, immigrants found mutual acceptance, fostered through houses of worship and friendships between US-born children and their non-Muslim neighbors.

Smejkal’s best friend was Catholic, and her father kept beef hot dogs in the kitchen to respect the Muslim prohibition against pork.

Smejkal’s father, in turn, made sure Friday meals included fish sticks.

‘Being Muslim’

The Muslim presence across the Midwest grew exponentially after a 1965 immigration law eliminated the quotas that had blocked arrivals from many parts of the world since the mid-1920s, Curtis said.

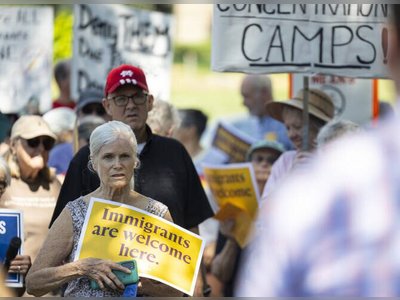

Immigration, including from Muslim countries, remains a contentious issue, even as Muslim communities flourish and increase their political influence in major cities like Minneapolis and Detroit.

Becoming Midwesterners

Faroz Waziri jokes that he and his wife Mena might have been the first Afghans in town when they came in the mid-2010s on a special visa for those who had worked for the US armed forces overseas.

After struggling with ‘culture shock’ and language barriers, they’ve become naturalized US citizens, and he’s the refugee resources manager at a non-profit founded by Catholic nuns.

These tensions are familiar for the descendants of the city’s first Muslim settlers, like Aossey, who keeps exhibit panels about Lebanese immigration and integration in the same garage where he stores ATVs on his recreational farm.

‘My story is the American story,’ Aossey said.

‘It’s not the Islamic story.’

The descendants of Lebanese immigrants who constructed ‘the Mother Mosque’ almost a century ago — along with newcomers from Afghanistan, East Africa and beyond — are defining what it can mean to be both Muslim and American in the nation’s heartland just as heightened conflicts in the Middle East fuel tensions over immigration and Islam in the United States.

Standing by the door in a gold-embroidered black robe, Fatima Igram Smejkal greeted the faithful with a cheerful ‘salaam’ as they hurried into the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids for Friday prayers.

In 1934, her family helped open what the National Register of Historic Places calls ‘the first building designed and constructed specifically as a house of worship for Muslims in the United States.’

Muslims attend Friday prayer at the Islamic Center of Cedar Rapids on Friday, Aug. 8, 2025, in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

(AP)

The community now gathers in the Islamic Center.

It was built in the 1970s when they became too many for the Mother Mosque’s living-room-sized prayer hall, and now they’re have outgrown its prayer hall, as well.

Hundreds of fifth-generation Muslim Iowans, recent refugees and migrants pray on industrial carpets rolled onto the gym’s basketball court — the elderly on walkers, babies in car seats, women in headscarves and men sporting headgear from African kufi and Afghan pakol caps to baseball hats.

This physical space where diverse groups gather helps sustain community as immigrants try to preserve their heritage while assimilating into US culture and society.

‘Mother Mosque’

Tens of thousands of young men, both Christians and Muslims, settled in booming Midwestern towns after fleeing the Ottoman Empire, many with little more than a Bible or a Qur’an in their bags.

They often worked selling housewares off their backs to widely scattered farms, earning enough to buy horses and buggies, and then opened grocery stores.

GROWING UP MUSLIM IN AMERICA

Muslims sometimes faced institutional discrimination.

After serving in World War II, Smejkal’s father, Abdallah Igram, successfully campaigned for soldiers’ dog tags to include Muslim as an option, along with Catholic, Protestant and Jewish.

But in Cedar Rapids, immigrants found mutual acceptance, fostered through houses of worship and friendships between US-born children and their non-Muslim neighbors.

Smejkal’s best friend was Catholic, and her father kept beef hot dogs in the kitchen to respect the Muslim prohibition against pork.

Smejkal’s father, in turn, made sure Friday meals included fish sticks.

‘Being Muslim’

The Muslim presence across the Midwest grew exponentially after a 1965 immigration law eliminated the quotas that had blocked arrivals from many parts of the world since the mid-1920s, Curtis said.

Immigration, including from Muslim countries, remains a contentious issue, even as Muslim communities flourish and increase their political influence in major cities like Minneapolis and Detroit.

Becoming Midwesterners

Faroz Waziri jokes that he and his wife Mena might have been the first Afghans in town when they came in the mid-2010s on a special visa for those who had worked for the US armed forces overseas.

After struggling with ‘culture shock’ and language barriers, they’ve become naturalized US citizens, and he’s the refugee resources manager at a non-profit founded by Catholic nuns.

These tensions are familiar for the descendants of the city’s first Muslim settlers, like Aossey, who keeps exhibit panels about Lebanese immigration and integration in the same garage where he stores ATVs on his recreational farm.

‘My story is the American story,’ Aossey said.

‘It’s not the Islamic story.’